All products are independently tested by the teams of Reliable Sporting. We may earn an affiliate commission if you buy through our links. Why trust us?

The baseball helmet: amidst the crack of the bat and the roar of the crowd, one unsung hero silently guards players from potential injury. In the world of sports, where speed, strategy, and precision collide, baseball stands as an embodiment of America’s favorite pastime. Let’s journey through time with us, Reliable Sporting, to uncover the intriguing history and evolution of these protective headgear that have become an integral part of the game.

Beginning Concepts (1905-1920)

The idea of a protective baseball headgear was relatively new in the early 1900s. A man by the name of Mogridge created the first protective headwear in 1905, and he was granted patent No. 780899 for his creation, which he dubbed the “head protector.” This was the first attempt at creating a batting helmet that looked like an “inflatable boxing glove” that covered the batter’s head. A few years later, in 1908, the renowned Hall of Fame catcher Roger Bresnahan invented the leather batting helmet in response to his own tragic pitch-related head injury.

Compared to the sturdy helmets of today, these early attempts at protective gear were, at best, crude, more like protective earmuffs. They mostly protected the areas around the ears and temples. Bresnahan even tried using a head protector made of aluminum that was covered in fake hair for the back of the head. It is still being determined if this odd device was ever used in the field.

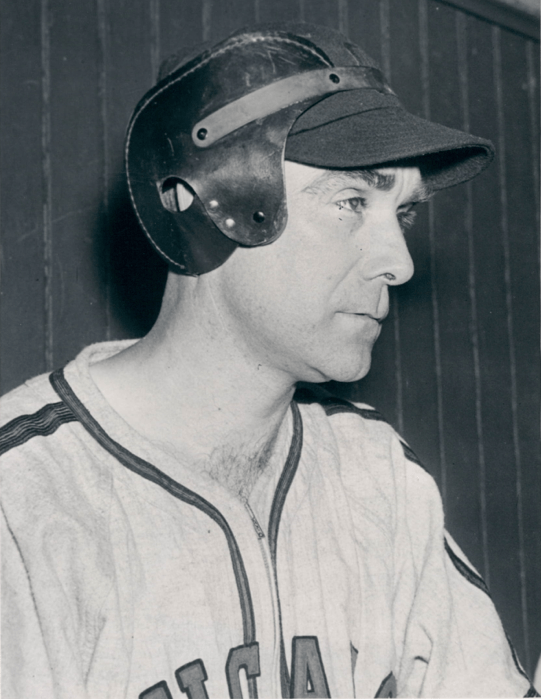

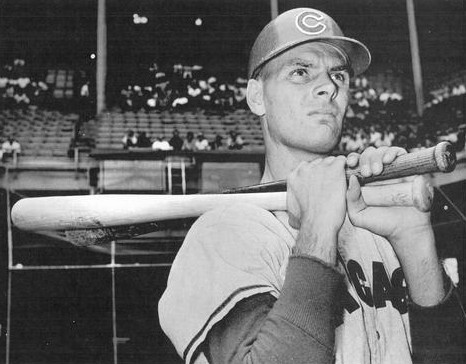

Head protection was only sporadically adopted in the late 1900s. In 1908, first baseman/manager Frank Chance of the Chicago Cubs and shortstop Freddy Parent of the Chicago White Sox took different measures to protect themselves. Chance was as safe as a bandaged sponge. That could have been better protection. After suffering a severe head injury during a game in 1911, minor league player Joe Bosk of the Utica Utes adopted head protection in 1914.

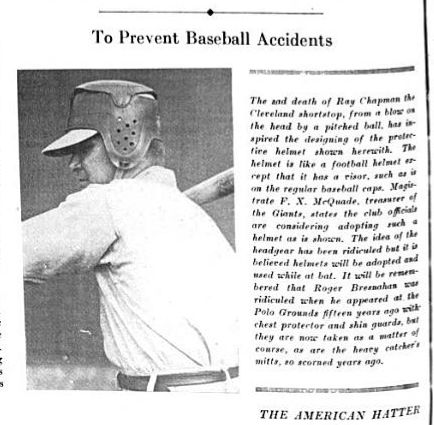

In spite of Ray Chapman’s tragic death in 1920 from a beaning incident, protective headgear was still a rare sight in the major leagues. A syndicated news article that year claimed that Frank McQuade, the secretary of the New York Giants, and other baseball executives were pushing for the mandatory use of batting helmets.

However, the report stated that players still needed to take to wearing helmets. The Philadelphia Phillies’ manager Pat Moran did something groundbreaking in 1921 when he gave his players hats with cork cushions. The Philadelphia Athletics manager, Connie Mack, also endorsed the use of protective headgear during this period.

Renewed Interest (1930-1950)

Baseball players’ safety received more attention in the 1930s, especially in light of head injuries. A seminal event happened in 1936 when a pitch struck Black league player Willie Wells in the temple, rendering him unconscious. The very next day, Wells showed incredible fortitude by playing a game while wearing a modified construction hard hat as protective gear, defying medical advice.

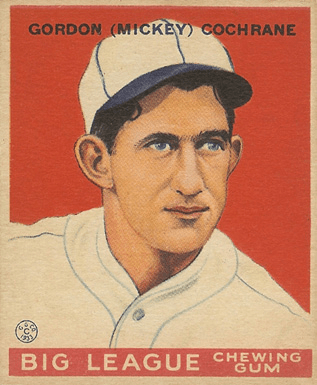

The pivotal moment occurred in 1937 after a disastrous incident involving Detroit Tigers Hall of Fame catcher Mickey Cochrane. Bump Hadley of the New York Yankees pitched Cochrane a pitch on May 25, 1937 that broke his skull and almost killed him. The use of protective batting helmets is urgently needed in light of this terrifying event. Cochrane himself strongly advocated for making such helmets mandatory for players.

The Cleveland Indians and Philadelphia Athletics were early adopters of helmet wear, experimenting with leather and polo helmets just a week after Cochrane’s injury on June 1, 1937. Although there is no hard proof that these were worn in actual games, their managers used batting practice to test the use of helmets on their players. The Western League’s Des Moines Demons hold the distinction of being the first team ever recorded to wear helmets during a game, if only momentarily.

When the International League adopted helmet use wholeheartedly in 1939, it was a historic moment for professional baseball. A “safety cap or helmet” was added to the official equipment list. The game’s safety evolution reached a turning point when Buster Mills became the first player in the league to wear a helmet.

Major League Baseball helmet laws were alluded to in 1940 during talks held during the MLB All-Star Game in Chicago. With great expectations that the league would accept it, National League President Ford Frick unveiled a new helmet design. He made it clear that wearing a batting helmet was essential to avoiding head injuries. Still, August 22, 1940, saw Jackie Hayes become the first player to wear a helmet during a real game, despite these conversations.

The real change occurred in 1941 when the National League mandated that all teams wear helmets during spring training, thanks to the influence of George Bennett, a brain surgeon from Johns Hopkins University. The Brooklyn Dodgers made the ground-breaking announcement that their players would wear helmets during regular season games on March 8, 1941. On April 26, 1941, the Washington Senators did the same, making history as the only two teams to wear batting helmets during the regular season. In June 1941, the Chicago Cubs and the New York Giants joined this safety initiative.

Tradition persisted despite hopes that this would lead to widespread adoption. The Pittsburgh Pirates didn’t make the audacious decision to require their players to wear helmets until 1953. This endeavor was led by their general manager, Branch Rickey, a former Dodger, and Charlie Muse created a helmet that was modeled after a hard hat worn by miners. When Milwaukee Braves first baseman Joe Adcock was hit by a pitch in 1954 and survived because of his helmet, there was a surge in interest in plastic protective caps.

Baseball, at all levels, saw a change in attitude toward helmet use in the 1950s. In the first part of the 1950s, Little League Baseball required all of its players to wear safety helmets. All players had to wear batting helmets when the National League adopted a similar rule in 1956. The movement gained momentum in 1958 when the American League joined, and both leagues adopted it as a universal rule. Baseball players embraced the new safety measure with great vigor, in contrast to the NHL at the time, which encountered opposition to its use.

![After having his jaw broken, Twins catcher Earl Battey wore this attachment to protect himself. [ESPN]](https://reliablesporting.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/10/image-14.png)

Major League Baseball made the final switch to helmet use, which was strictly required in December 1970. A grandfather clause allowed veteran players to choose whether or not to wear a helmet. Interestingly, Bob Montgomery of the Boston Red Sox, who was last seen in a Major League game in 1979, is the most recent player to bat without a helmet. Interestingly, the NHL implemented a grandfather clause for veteran players in 1979 and made helmet use mandatory. The growing significance of keeping baseball players safe on the field is reflected in this major change in safety procedures.

Refinements (1960-2000)

Baseball helmets underwent substantial changes in the 1960s, adopting improved safety features.

Jim Lemon made history in 1960 when he was the first player to play a Major League game wearing the new Little League helmet. These helmets were designed to withstand the impact of a baseball hitting them at up to 120 miles per hour (190 km/h), and they have earflaps on both sides. Jimmy Piersall became the second Major League player to wear this unique helmet when he did the same just a month later.

As Major League Baseball began using these helmets on a large scale, the early 1960s saw the beginning of significant changes. Pitcher Earl Battey was in serious condition on July 23, 1961, after being struck in the face by a pitch that broke his bone. Using an improvised earflap, Battey returned to the field ten days later, trying to protect the injured area.

The experiment, though, was short-lived since he complained that it interfered with his vision. In a related development, Jimmie Hall and Tony Oliva used homemade face shields for batting practice during the 1965 World Series.

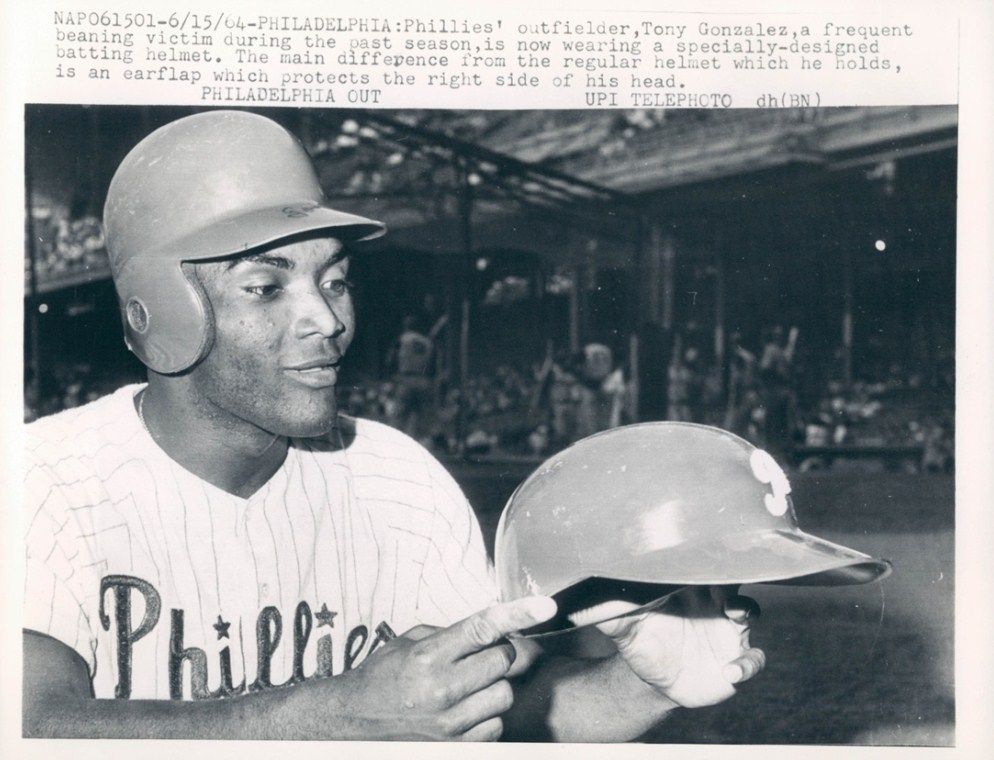

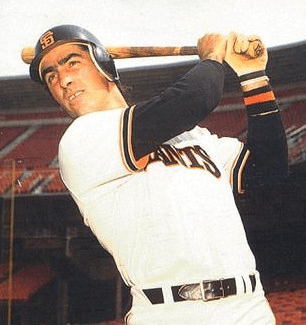

Tony González of the Phillies introduced a game-changing idea in 1964 with the introduction of the pre-molded earflap helmet, which turned the tide. This invention represented a turning point in the development of headgear safety. Earflaps were previously made up on the fly based on the preferences of the players. Because González was among the league’s top ten in this category and was frequently the target of hit-by-pitches, a custom helmet was made for him.

Earflap helmets were standard in amateur baseball, but getting into Major League Baseball required a lot of work. A few participants felt that the earflap’s constant presence in their field of vision was annoying. Some players, however, persisted and showed fortitude in the face of peril. For example, Ron Santo was the first player in the major leagues to wear an earflap helmet after being hit by a pitch that fractured his left cheekbone in 1966.

As time went on, new innovations appeared. Legendary infielder Brooks Robinson started wearing an ear-flapped helmet during the 1970 season. But Robinson discovered that his visibility was limited not only by the earflap but also by the helmet’s brim. He made the astute decision to use a hacksaw to cut off the majority of the brim, a change he accepted for the duration of his career.

A turning point was reached when Robert Crow, a 1970s Atlanta Braves plastic and reconstructive surgeon, invented the “C-Flap.” In order to add even more safety, this gadget—named after Crow—that shields the cheek could be fastened to the ear flap of a regular helmet. The “C-Flap” was not widely embraced at first, but in the ensuing decades, it would prove to be an essential addition to helmet safety.

After breaking his cheek and jaw bones in a collision at home plate in 1978, Dave Parker of the Pittsburgh Pirates made headlines when he resorted to wearing a hockey mask at the plate. This was a one-game experiment that Parker quickly abandoned to investigate wearing a helmet with a two-bar football facemask attached. He also experimented with a helmet that had the Dungard 210 facemask, a different football facemask, fitted inside of it.

Notable batters who wore modified batting helmets without a “C-Flap” were Otis Nixon (1998), Charlie Hayes (1994), Ellis Valentine (1980), and Gary Roenicke (1979). Terry Steinbach of the Oakland A’s was the first player to wear the “C-Flap,” having turned to it in 1988 following an orbital bone break sustained in a pregame accident.

About a month after his successful facial surgery, Steinbach made a comeback to the game with the added protection of the “C-Flap.” Other players were prompted by his initiative to use the “C-Flap” for extra security. Notably, Yadier Molina (2016) and Jason Heyward (2013) adopted the “C-Flap” for life. Molina did so as a preventative measure, even though he had never had a facial injury before.

When Baltimore Orioles player Gary Roenicke was hit in the face in 1979 and needed twenty-five stitches, he came up with a creative way to affix a football helmet’s facemask to his batting helmet. Roenicke revealed that the face mask from Baltimore Colts quarterback Bert Jones’ helmet was repurposed by the Orioles trainers and fastened to his batting helmet. Up until 1981, Roenicke wore this altered helmet.

All new players were required by Major League Baseball to wear helmets with at least one earflap in 1983. But if they wanted to, grandfathered players could choose to wear helmets without ear flaps. Although it wasn’t required, players in the major leagues were also allowed to don double earflap helmets.

The final player to wear a helmet without a flap was Tim Raines in the 2002 campaign. The Baseball Hall of Fame currently has his helmet from that era on display. Until their retirement, several players chose to wear flapless helmets, including Tim Wallach (retired in 1996), Ozzie Smith, and Gary Gaetti (retired in 2000). The last active player qualified to wear a helmet without flaps was Julio Franco, who ended his career in May of 2008, but he always opted for an ear-flapped helmet.

Some players, mostly switch hitters like Willie McGee, Terry Pendleton, Vince Coleman, Mark Bellhorn, Shane Victorino, Orlando Hudson, and Jed Lowrie, also chose to wear double earflap helmets. These switch-hitting players thought it was helpful to have the extra protection.

Modern Day Baseball Helmets (2000-Present)

Baseball helmets are still evolving as we enter the new millennium, meeting both traditional and modern demands.

Celebrated as “Hank Aaron Day,” April 8, 2004, in Atlanta marked the 30th anniversary of Hank Aaron’s legendary 715th home run. Rafael Furcal, the shortstop for the Braves, made a symbolic move at the plate by donning a helmet devoid of an earflap. This memorial to Hank Aaron honored the time when ear-flapped helmets were not common. Aaron’s remarkable career spanned the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. But Umpire Bill Welke stepped in quickly, demanding that Furcal wear a helmet with the protective flap instead.

Major League Baseball made history in 2005 when it unveiled a new batting helmet design—the first noteworthy alteration in almost thirty years. Players were spotted wearing the cutting-edge “molded crown” helmet, which has bigger ear holes, back vents, and side vents, during the All-Star Game in Detroit. While most players have switched to these more contemporary helmets, some, like Ryan Howard, have stuck with the classic design.

The no-flap helmet still has a place in the game despite these developments. In order to protect their heads when receiving pitches, catchers often wear facemasks in addition to flapless helmets. Sometimes, when in a defensive position, players—not just catchers—choose to wear batting helmets without earflaps. Players who have a greater chance of suffering a head injury frequently make this unorthodox decision.

For instance, after requiring emergency surgery for a cerebral aneurysm while attending Washington State University, former major league player John Olerud started this practice. Another historical example is when Richie Allen started wearing a helmet on the field after getting struck by objects that fans threw at him.

Other positions on the baseball field are also subject to the same dedication to player safety. When performing their duties on the field, Major League bat-boys and bat-girls, along with ball boys and ball girls, are required to don helmets rather than traditional caps. To increase their protection, a lot of them decide to wear helmets without flaps.

After being hit by a batted ball and dying, first base coach Mike Coolbaugh of the Tulsa Drillers was a tragic figure in the baseball community in 2007. The wearing of helmets by base coaches has been the subject of heated discussions following this incident. Rene Lachemann, the coach of the Oakland Athletics, responded by taking a bold stance and wearing a helmet while coaching third base.

Major League Baseball announced after the 2007 season that all coaches would have to wear helmets starting in the 2008 campaign. It is noteworthy, though, that some coaches disagreed with this choice, including Los Angeles Dodgers’ Larry Bowa.

Major League Baseball made a big move in 2009 to shield players from the rising number of head injuries and concussions. The S100 baseball helmet, so named because of its exceptional impact resistance, was introduced by Rawlings. The force of a baseball traveling at 100 miles per hour (160 km/h) from a distance of only 2 feet (0.6 m) was intended to be withstood by this helmet.

Although the S100 helmet provided better protection, some players objected to it, saying it made them look like goofballs. However, some, like Mets third baseman David Wright, welcomed the extra security it offered when they batted.

The MLB-MLBPA Collective Bargaining Agreement required the MLB-S100 Pro Comp to be introduced in 2013, ushering in a new era. This reaffirmed the highest level of the sport’s commitment to player safety.

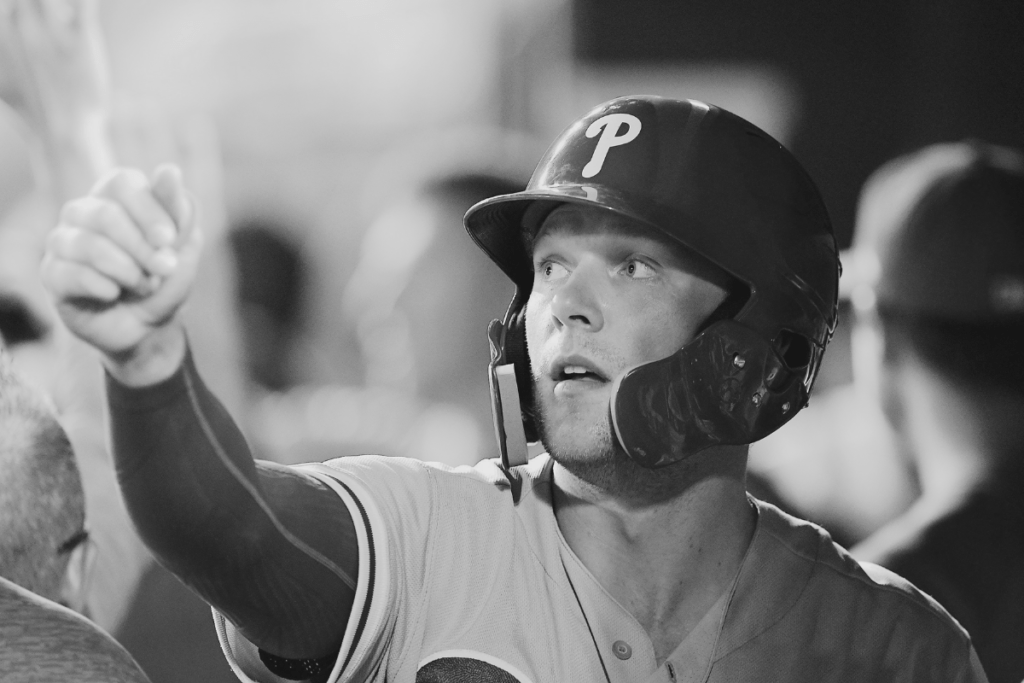

2018 saw the emergence of even more innovation when well-known MLB players like Mike Trout and Bryce Harper adopted the “C-flap.” Attached to the earflap, this creative Markwort-designed extension offers more jaw coverage. Major League Baseball players took to the “C-flap” with such rapidity that it inspired helmet manufacturers like Rawlings and Easton to create helmets that included integrated earflap extensions that looked like the “C-flap.”

Slugger Rhys Hoskins of the Philadelphia Phillies had a bad incident on May 28, 2018, during a game against the LA Dodgers, where he fouled a ball off his own face and broke his jaw. Hoskins, a 25-year-old athlete, had to make the tough choice of missing four to six weeks of play or coming back from a 10-day stint on the disabled list with a C-Flap on both sides for complete protection. Choose the latter, and Hoskins returned to action an astonishing 12 days following his injury, demonstrating the value of the double-C-Flap configuration.

Double-earflap batting helmets are now required by many baseball leagues, including Minor League Baseball. Interestingly, Major League Baseball only permits the use of one earflap, honoring custom while putting player safety first.

Browse more: Baseball Bats